Profile

Leeat Granek

Birth:

1979

Training Location(s):

PhD, York University (2009)

MA, York University (2003)

BA, York University (2001)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Department of Public Health (2012-present)

Hospital for Sick Children, Psychology, University of Toronto (2011)

McMaster Children’s Hospital, Pediatrics (2009-2011)

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (2008-2009)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Career Focus:

Psycho-oncology; grief and loss; health psychology; feminist psychology; medical education; women’s physical and mental health; qualitative methods; history and theory of psychological disorders and practice.

Biography

Leeat Granek was born in Montreal, Quebec, to working-class parents who had recently immigrated to Canada. Her class background shaped what she perceived to be possible. Since no one in her family had attended university, pursuing higher education was not an obvious or straightforward path for her: “The only reason I went [to university] was because other people around me were going [from] the school that I was in, but I had no [real] direction because I had no idea what was possible.” However, she describes this lack of direction as a “gift,” as it allowed her to follow her desires and let curiosity guide her choices.

Her awareness of gendered power dynamics was amplified when she took women’s studies courses at York University and read works such as The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf. Her growing passion for feminism led her to attend a “feminist leadership retreat” at The Woodhull Institute for Ethical Leadership, directed by Naomi Wolf. The institute’s purpose was to help women from diverse backgrounds develop their leadership skills by teaching them how to effectively express themselves and create supportive professional and personal networks. The network she built at Woodhull helped Granek overcome the boundaries of a working-class background by connecting her to other academics and leaders in the professional world: “Anytime anybody needs anything, women who are located all over the world help each other access what they need - whether it is a job, a place to stay, or a connection.” Furthermore, she says that these relationships enabled her to “see all of the potential paths that [she] couldn’t see before, that [she] had no access to before because [she] had no one to talk to about it, no one to encourage or push [her].”

Granek thrived in university, noting that “I was going to stay in school and do what I loved until I didn’t love it anymore.” Acting on this conviction, she decided to pursue graduate studies. She completed a Masters in Interdisciplinary Studies and a PhD in the History and Theory of Psychology, both at York University in Toronto, precisely because they “allowed for so much freedom.” In these programs she felt she could not only ask the questions which most piqued her curiosity, but also analyze them in a critical manner. During her MA she became interested in women’s narratives of depression. This work revealed the “links between the social world…and what was going on interpersonally for people.” At this time she began studying qualitative methods, specifically grounded theory, with her professor and mentor David Rennie.

In her PhD research, her area of focus changed from the history and theory of feminist psychology to examining the psychological construct of grief. This shift occurred when, “half way through my PhD program, my mom died of cancer and my direction shifted simply because I was so immersed in my own grief.” Granek then noticed a very big gap between what she was experiencing as a griever and what society was expecting of her. With this experience as a springboard, her dissertation critically examined the pathologization of grief and what it means to be a griever today. Now a professor in the Department of Public Health at Ben-Gurion University in Israel, she has continued her research on grief, examining the influence of gender-specific expectations, culture, politics, and notions of ideal citizenship in the Israeli context.

I saw in all of these rituals and traditions how the women's role was to be the holders of this collective grief and at the same time they are also pathologized for it. The types of grievers that are pathologized are the ones that are overly expressive of their grief, that are taking too long with their grieving process, that are too intense in their grief, that are not willing to go back to things as they were before. So women are caught up in this double bind…There is this dual expectation that they both be the expressers and the holders of grief for the family, for the society, for the culture, for the nation, and so on - but, not too much. When it is time to put it away, then it is time to put it away. There is this bind that is very hard to get out of, that you are both required to be this expresser and also required to keep it in check. If you can't keep it in check, then you are given an anti-depressant.

Granek has also written on oncologists’ experience of patient bereavement, arguing that society does not allow for the time and space that this process takes and instead creates shame around it, which is detrimental to physicians and negatively affects how they are able to interact with their patients.

What I'm trying to do is, in the bigger picture, is to give people a better death.… I noticed because of my own experience with my mom and the oncologists in her life that the relationships in medicine were starting to be eroded and progressively so as the Canadian health care system has become more corporatized…Even though it is a socialized healthcare system… The relationships [between patient and provider] are being erased. So part of looking at grief in oncologists over patient death is saying these relationships are real and they are important. They are important not just for the well-being of the oncologist…but also important to the quality of care that people are getting and the quality of death that they are experiencing.

In order to reach the populations most affected by the results of her research, Granek publishes strategically in both academic venues and the popular press, often translating her research for media such as the New York Times and Huffington Post: "I always try to write…and speak two languages because the goal at the end of the day is to communicate so people can hear you. In order to improve women's lives and the lives of our participants, we need to speak clearly first of all and in ways that people can hear."

Upon reflection, she realizes that she has, at least in part, learned to take up her mother's early advice to sometimes “go around” obstacles rather than attacking them head-on. That is, she has learned how to speak to academics in ways that effectively convey the importance of attending to gender dynamics and socio-political contexts when conducting psychological research, as well as how to simplify complex jargon in order to make her research accessible to clinicians, their patients, and the general public.

As Granek moves into the next phases of her career, she takes with her the lessons she learned at the Woodhull Institute. A strong peer support network remains a major component of her academic success and fuels her drive to both continue and expand her areas of interest: “I think finding a community of really supportive, like-minded women is mandatory” in order to “follow your passions and to stay really true to…the things that are going to lift you up.” She also recommends that academics try to maintain a work-life balance:

To be a whole human being and to be a really good thinker, you need to get away from the computer. The goal should not be to produce as much as possible. The goal needs to be to produce the most innovative, thought provoking, inspiring, engaged kind of work that you can produce and that is totally contradictory to the messages that we get…But I really think that the work-life balance is very important in developing yourself as a thinker. Our job is to develop ourselves as human beings in order to produce good work.

by Prapti Giri (2015)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Granek, L, Bartels U., Scheinemann K., Labrecque M., Barrera M. (2015). Grief reactions and impact of patient death on pediatric oncologists. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(1), 134-142.

Granek, L. (2014). The heritability of cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 2270-2271.

Granek, L. (2014). Mourning sickness: The politicizations of grief. Review of General Psychology, 18(2), 61-68.

Granek, L., Barrera, M., Shaheed, J., Nicholas, D., Beaune, L., D’Agostino, N.M., Bouffet, E., Antle, B. (2013).Trajectory of parental hope when a child has difficult to treat cancer: A prospective qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology, 22(11), 2436-44.

Granek, L. (2013). Disciplinary wounds: Has grief become the identified patient for a fieldgone awry? Journal of Loss & Trauma, 18, 3.

Granek, L., Tozer, R., Mazzotta, P., Ramjaum, A. & Krzyzanowska, M. (2012). Nature and impact of grief over patient loss on oncologists’ personal and professional Lives. JAMA Internal Medicine, ,172(12), 964-966.

Granek, L. & Fergus, K. (2012). Resistance, agency, and liminality in women’s accounts of help seeking upon discovery of an abnormal breast symptom. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 1753-1761.

Granek, L. (2010).Grief as pathology: The evolution of grief theory in psychology from Freud to the present. History of Psychology, 13, 46-73.

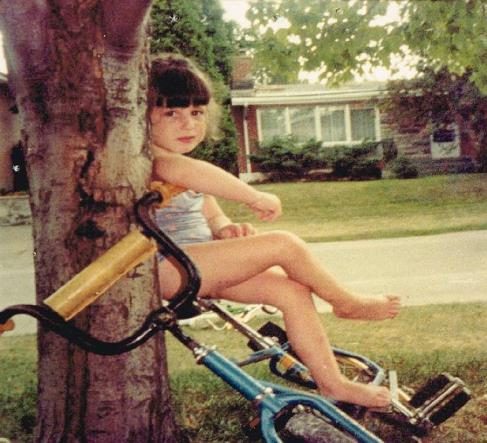

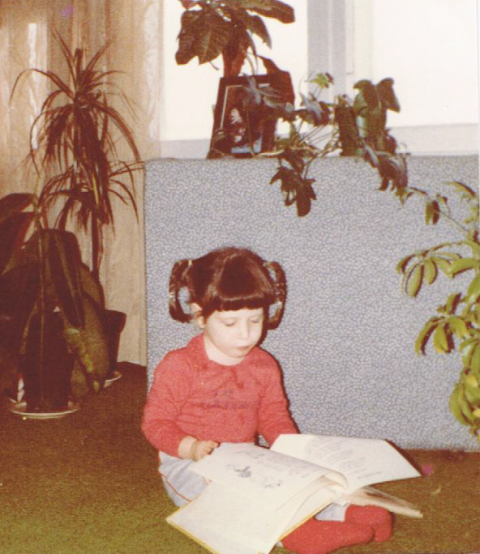

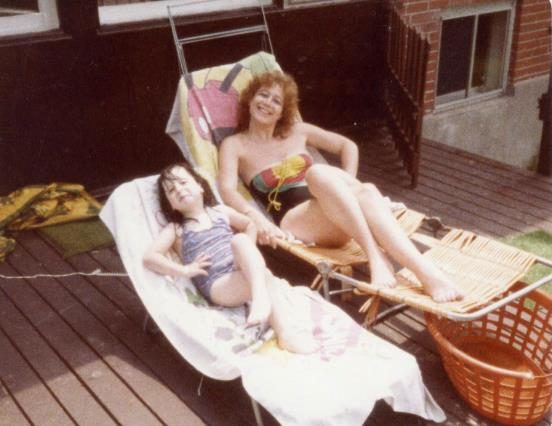

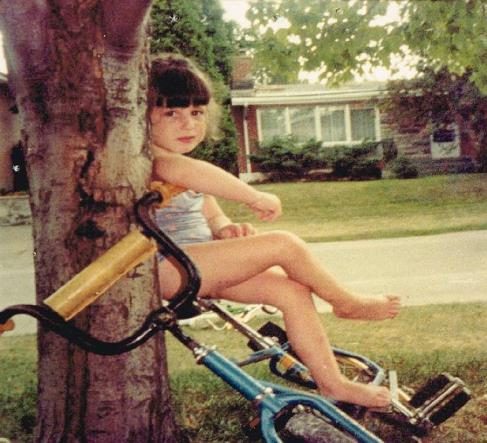

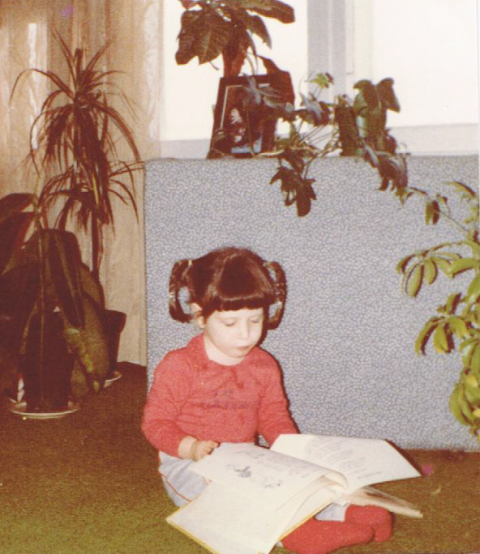

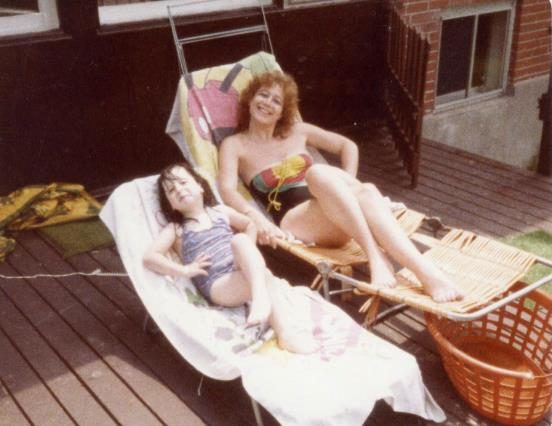

Photo Gallery

Leeat Granek

Birth:

1979

Training Location(s):

PhD, York University (2009)

MA, York University (2003)

BA, York University (2001)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Department of Public Health (2012-present)

Hospital for Sick Children, Psychology, University of Toronto (2011)

McMaster Children’s Hospital, Pediatrics (2009-2011)

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (2008-2009)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

Career Focus:

Psycho-oncology; grief and loss; health psychology; feminist psychology; medical education; women’s physical and mental health; qualitative methods; history and theory of psychological disorders and practice.

Biography

Leeat Granek was born in Montreal, Quebec, to working-class parents who had recently immigrated to Canada. Her class background shaped what she perceived to be possible. Since no one in her family had attended university, pursuing higher education was not an obvious or straightforward path for her: “The only reason I went [to university] was because other people around me were going [from] the school that I was in, but I had no [real] direction because I had no idea what was possible.” However, she describes this lack of direction as a “gift,” as it allowed her to follow her desires and let curiosity guide her choices.

Her awareness of gendered power dynamics was amplified when she took women’s studies courses at York University and read works such as The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf. Her growing passion for feminism led her to attend a “feminist leadership retreat” at The Woodhull Institute for Ethical Leadership, directed by Naomi Wolf. The institute’s purpose was to help women from diverse backgrounds develop their leadership skills by teaching them how to effectively express themselves and create supportive professional and personal networks. The network she built at Woodhull helped Granek overcome the boundaries of a working-class background by connecting her to other academics and leaders in the professional world: “Anytime anybody needs anything, women who are located all over the world help each other access what they need - whether it is a job, a place to stay, or a connection.” Furthermore, she says that these relationships enabled her to “see all of the potential paths that [she] couldn’t see before, that [she] had no access to before because [she] had no one to talk to about it, no one to encourage or push [her].”

Granek thrived in university, noting that “I was going to stay in school and do what I loved until I didn’t love it anymore.” Acting on this conviction, she decided to pursue graduate studies. She completed a Masters in Interdisciplinary Studies and a PhD in the History and Theory of Psychology, both at York University in Toronto, precisely because they “allowed for so much freedom.” In these programs she felt she could not only ask the questions which most piqued her curiosity, but also analyze them in a critical manner. During her MA she became interested in women’s narratives of depression. This work revealed the “links between the social world…and what was going on interpersonally for people.” At this time she began studying qualitative methods, specifically grounded theory, with her professor and mentor David Rennie.

In her PhD research, her area of focus changed from the history and theory of feminist psychology to examining the psychological construct of grief. This shift occurred when, “half way through my PhD program, my mom died of cancer and my direction shifted simply because I was so immersed in my own grief.” Granek then noticed a very big gap between what she was experiencing as a griever and what society was expecting of her. With this experience as a springboard, her dissertation critically examined the pathologization of grief and what it means to be a griever today. Now a professor in the Department of Public Health at Ben-Gurion University in Israel, she has continued her research on grief, examining the influence of gender-specific expectations, culture, politics, and notions of ideal citizenship in the Israeli context.

I saw in all of these rituals and traditions how the women's role was to be the holders of this collective grief and at the same time they are also pathologized for it. The types of grievers that are pathologized are the ones that are overly expressive of their grief, that are taking too long with their grieving process, that are too intense in their grief, that are not willing to go back to things as they were before. So women are caught up in this double bind…There is this dual expectation that they both be the expressers and the holders of grief for the family, for the society, for the culture, for the nation, and so on - but, not too much. When it is time to put it away, then it is time to put it away. There is this bind that is very hard to get out of, that you are both required to be this expresser and also required to keep it in check. If you can't keep it in check, then you are given an anti-depressant.

Granek has also written on oncologists’ experience of patient bereavement, arguing that society does not allow for the time and space that this process takes and instead creates shame around it, which is detrimental to physicians and negatively affects how they are able to interact with their patients.

What I'm trying to do is, in the bigger picture, is to give people a better death.… I noticed because of my own experience with my mom and the oncologists in her life that the relationships in medicine were starting to be eroded and progressively so as the Canadian health care system has become more corporatized…Even though it is a socialized healthcare system… The relationships [between patient and provider] are being erased. So part of looking at grief in oncologists over patient death is saying these relationships are real and they are important. They are important not just for the well-being of the oncologist…but also important to the quality of care that people are getting and the quality of death that they are experiencing.

In order to reach the populations most affected by the results of her research, Granek publishes strategically in both academic venues and the popular press, often translating her research for media such as the New York Times and Huffington Post: "I always try to write…and speak two languages because the goal at the end of the day is to communicate so people can hear you. In order to improve women's lives and the lives of our participants, we need to speak clearly first of all and in ways that people can hear."

Upon reflection, she realizes that she has, at least in part, learned to take up her mother's early advice to sometimes “go around” obstacles rather than attacking them head-on. That is, she has learned how to speak to academics in ways that effectively convey the importance of attending to gender dynamics and socio-political contexts when conducting psychological research, as well as how to simplify complex jargon in order to make her research accessible to clinicians, their patients, and the general public.

As Granek moves into the next phases of her career, she takes with her the lessons she learned at the Woodhull Institute. A strong peer support network remains a major component of her academic success and fuels her drive to both continue and expand her areas of interest: “I think finding a community of really supportive, like-minded women is mandatory” in order to “follow your passions and to stay really true to…the things that are going to lift you up.” She also recommends that academics try to maintain a work-life balance:

To be a whole human being and to be a really good thinker, you need to get away from the computer. The goal should not be to produce as much as possible. The goal needs to be to produce the most innovative, thought provoking, inspiring, engaged kind of work that you can produce and that is totally contradictory to the messages that we get…But I really think that the work-life balance is very important in developing yourself as a thinker. Our job is to develop ourselves as human beings in order to produce good work.

by Prapti Giri (2015)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Granek, L, Bartels U., Scheinemann K., Labrecque M., Barrera M. (2015). Grief reactions and impact of patient death on pediatric oncologists. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(1), 134-142.

Granek, L. (2014). The heritability of cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 2270-2271.

Granek, L. (2014). Mourning sickness: The politicizations of grief. Review of General Psychology, 18(2), 61-68.

Granek, L., Barrera, M., Shaheed, J., Nicholas, D., Beaune, L., D’Agostino, N.M., Bouffet, E., Antle, B. (2013).Trajectory of parental hope when a child has difficult to treat cancer: A prospective qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology, 22(11), 2436-44.

Granek, L. (2013). Disciplinary wounds: Has grief become the identified patient for a fieldgone awry? Journal of Loss & Trauma, 18, 3.

Granek, L., Tozer, R., Mazzotta, P., Ramjaum, A. & Krzyzanowska, M. (2012). Nature and impact of grief over patient loss on oncologists’ personal and professional Lives. JAMA Internal Medicine, ,172(12), 964-966.

Granek, L. & Fergus, K. (2012). Resistance, agency, and liminality in women’s accounts of help seeking upon discovery of an abnormal breast symptom. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 1753-1761.

Granek, L. (2010).Grief as pathology: The evolution of grief theory in psychology from Freud to the present. History of Psychology, 13, 46-73.