Profile

Alice Lee

Birth:

1859

Death:

1939

Training Location(s):

PhD, London University (1901)

BA, Bedford College for Women (1885)

BS, Bedford College for Women (1884)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Bedford College for Women (1886-1916)

Eugenics Records Office (1892-1907)

Galton Eugenics Laboratory (1907-1927)

Other Media:

Archival Collections

Alice Lee correspondence in Galton Archives, University College London, London, England.

Alice Lee correspondence in Pearson Papers, University College London, London, England.

Career Focus:

Craniometry; heredity; inheritance; statistics; eugenics.

Biography

Alice Lee was an early mathematician and statistician who worked in Karl Pearson's Biometric Laboratory. Lee attended Bedford College for Women from 1876-1884, where she was the first student to receive a B.Sc, in 1884. In 1885 she received a B.A. from Bedford, and she also attended London University shortly after it opened to women in 1878. As Margaret Tuke, a Bedford Administrator, later noted, "To us now these successes seem everyday and unimportant or of importance only to the individual. To believers in the higher education of women in the early 1880's intent on showing what women could do, each success was a matter for enthusiasm" (Love, 1978, p. 147).

Lee, who had demonstrated an aptitude for higher mathematics, stayed on at Bedford College, first as an assistant teacher in mathematics and physics, then as a research lecturer in applied mathematics. The size and age of the college meant that Bedford professors could not be too narrowly focused: Lee also assisted Greek and Latin classes and served as a resident helper at the college in return for free room and board.

Alice Lee's first contact with Karl Pearson came in 1892 when Pearson attacked Bedford College's academic standards in the Pall Mall Gazette, suggesting that the school be eliminated since it clearly fell below academic standards. As a result, Lee wrote to him defending the school. Lee was soon was assisting Pearson with his calculations, and was brought on as an assistant in the Biometric Laboratory in 1892. By 1895, she was attending his statistics lectures at University College London.

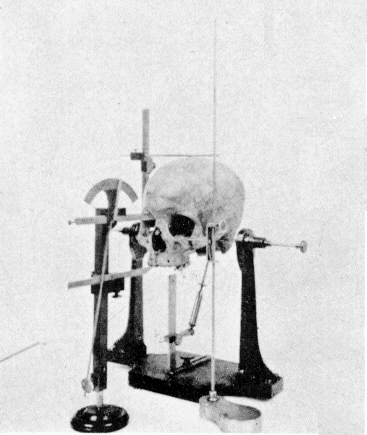

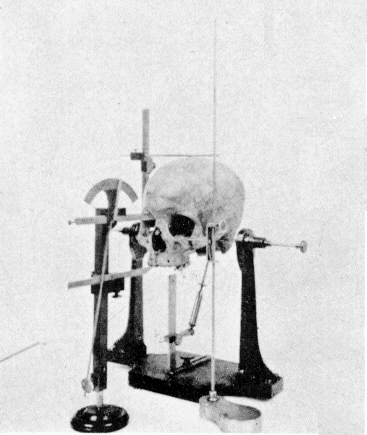

As Lee gained more knowledge about Pearson's statistical practices and biometry, she found that she was interested in craniometry, the study of skull capacity. Skull capacity was generally thought to be directly correlated with intelligence, with larger skulls indicating greater intelligence. This theory had both sexist implications: men (with their generally larger skulls) were smarter than women, and racist implications. Lee argued that the correlation between skull capacity and intelligence was an unjustified assumption, and that to test it, the skull capacity of living individuals of known intellectual powers should be measured. In order to do this, Lee created a formula of cranial measurements that could replace the traditional methods, which involved filling (empty) skulls with sand. Using her formula, Lee ranked the supposed intelligence of 35 leading anatomists who attended a meeting of the Anatomical Society in Dublin in 1898, in which their skulls were measured. Lee used the nonsensical results to argue that skull capacity was unrelated to eminence or intelligence. As Lee summarized her results: "arguments based on the relative brain weight of the two sexes require a more solid quantitative basis than they at present exhibit" (Love, 1978, p. 150). Instead, Lee believed that skull capacity was more likely a characteristic of racial 'type'. In this conviction she was not alone among many women who, though arguing strenuously against the sexist implications of craniometry, were unable to see beyond - and even endorsed - its racist implications.

When it came time for Lee to publish her thesis on the subject, she faced both skepticism about her conclusions and doubts about the originality of her work. Pearson staunchly supported her, and coached her on what to say to Francis Galton when she joined him for tea to discuss her thesis. Despite Galton's conviction of women's inferiority and his disagreement with Lee's conclusions, the tea was pleasant and Alice Lee received her degree, one of the first women to receive a Doctor of Science from London University in 1901.

During WWI Lee contributed to the war effort by calculating gun trajectories for the Munitions Inventions Department, and doing computing work for the Admiralty. Lee finally retired from Pearson's Laboratory in1927; she had worked voluntarily and largely unpaid for the last 10 years. Many of the tables she developed were used by statisticians for decades to come. In his request that Lee receive a government pension Karl Pearson wrote "few, if any women workers of her period have accomplished as large a bulk of first class research as Dr. Lee" (Love, 1978, p. 152).

by Elissa Rodkey (2011)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Alice Lee

Lee, A. (1902) Data for the problem of evolution in man: A first study of the correlation of the human skull. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. London, 255-264.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (5 July 1897). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution: On the relative variation and correlation in civilized and uncivilized races. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 61, 343-57.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (1901). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution--VIII. On the Inheritance of characters not capable of exact quantitative measurement. Philosophical Transactions, 195A, 79-150.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (February 1903). On the laws of inheritance in man. Biometrika, 2, 357-462.

Pearson, K., Lee, A., & Bramley-Moore, L. (1899). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution: VI Genetic (reproductive) selection: Inheritance of fertility in man, and of fecundity in Thoroughbred race-horses, Philosophical Transactions, 192A, 257-330.

About Alice Lee

Love, R. (1979). 'Alice in Eugenics-Land': Feminism and eugenics in the scientific careers of Alice Lee and Ethel Elderton. Annals of Science 36, 145-158.

Alice Lee

Birth:

1859

Death:

1939

Training Location(s):

PhD, London University (1901)

BA, Bedford College for Women (1885)

BS, Bedford College for Women (1884)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Bedford College for Women (1886-1916)

Eugenics Records Office (1892-1907)

Galton Eugenics Laboratory (1907-1927)

Other Media:

Archival Collections

Alice Lee correspondence in Galton Archives, University College London, London, England.

Alice Lee correspondence in Pearson Papers, University College London, London, England.

Career Focus:

Craniometry; heredity; inheritance; statistics; eugenics.

Biography

Alice Lee was an early mathematician and statistician who worked in Karl Pearson's Biometric Laboratory. Lee attended Bedford College for Women from 1876-1884, where she was the first student to receive a B.Sc, in 1884. In 1885 she received a B.A. from Bedford, and she also attended London University shortly after it opened to women in 1878. As Margaret Tuke, a Bedford Administrator, later noted, "To us now these successes seem everyday and unimportant or of importance only to the individual. To believers in the higher education of women in the early 1880's intent on showing what women could do, each success was a matter for enthusiasm" (Love, 1978, p. 147).

Lee, who had demonstrated an aptitude for higher mathematics, stayed on at Bedford College, first as an assistant teacher in mathematics and physics, then as a research lecturer in applied mathematics. The size and age of the college meant that Bedford professors could not be too narrowly focused: Lee also assisted Greek and Latin classes and served as a resident helper at the college in return for free room and board.

Alice Lee's first contact with Karl Pearson came in 1892 when Pearson attacked Bedford College's academic standards in the Pall Mall Gazette, suggesting that the school be eliminated since it clearly fell below academic standards. As a result, Lee wrote to him defending the school. Lee was soon was assisting Pearson with his calculations, and was brought on as an assistant in the Biometric Laboratory in 1892. By 1895, she was attending his statistics lectures at University College London.

As Lee gained more knowledge about Pearson's statistical practices and biometry, she found that she was interested in craniometry, the study of skull capacity. Skull capacity was generally thought to be directly correlated with intelligence, with larger skulls indicating greater intelligence. This theory had both sexist implications: men (with their generally larger skulls) were smarter than women, and racist implications. Lee argued that the correlation between skull capacity and intelligence was an unjustified assumption, and that to test it, the skull capacity of living individuals of known intellectual powers should be measured. In order to do this, Lee created a formula of cranial measurements that could replace the traditional methods, which involved filling (empty) skulls with sand. Using her formula, Lee ranked the supposed intelligence of 35 leading anatomists who attended a meeting of the Anatomical Society in Dublin in 1898, in which their skulls were measured. Lee used the nonsensical results to argue that skull capacity was unrelated to eminence or intelligence. As Lee summarized her results: "arguments based on the relative brain weight of the two sexes require a more solid quantitative basis than they at present exhibit" (Love, 1978, p. 150). Instead, Lee believed that skull capacity was more likely a characteristic of racial 'type'. In this conviction she was not alone among many women who, though arguing strenuously against the sexist implications of craniometry, were unable to see beyond - and even endorsed - its racist implications.

When it came time for Lee to publish her thesis on the subject, she faced both skepticism about her conclusions and doubts about the originality of her work. Pearson staunchly supported her, and coached her on what to say to Francis Galton when she joined him for tea to discuss her thesis. Despite Galton's conviction of women's inferiority and his disagreement with Lee's conclusions, the tea was pleasant and Alice Lee received her degree, one of the first women to receive a Doctor of Science from London University in 1901.

During WWI Lee contributed to the war effort by calculating gun trajectories for the Munitions Inventions Department, and doing computing work for the Admiralty. Lee finally retired from Pearson's Laboratory in1927; she had worked voluntarily and largely unpaid for the last 10 years. Many of the tables she developed were used by statisticians for decades to come. In his request that Lee receive a government pension Karl Pearson wrote "few, if any women workers of her period have accomplished as large a bulk of first class research as Dr. Lee" (Love, 1978, p. 152).

by Elissa Rodkey (2011)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Alice Lee

Lee, A. (1902) Data for the problem of evolution in man: A first study of the correlation of the human skull. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. London, 255-264.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (5 July 1897). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution: On the relative variation and correlation in civilized and uncivilized races. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 61, 343-57.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (1901). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution--VIII. On the Inheritance of characters not capable of exact quantitative measurement. Philosophical Transactions, 195A, 79-150.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (February 1903). On the laws of inheritance in man. Biometrika, 2, 357-462.

Pearson, K., Lee, A., & Bramley-Moore, L. (1899). Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution: VI Genetic (reproductive) selection: Inheritance of fertility in man, and of fecundity in Thoroughbred race-horses, Philosophical Transactions, 192A, 257-330.

About Alice Lee

Love, R. (1979). 'Alice in Eugenics-Land': Feminism and eugenics in the scientific careers of Alice Lee and Ethel Elderton. Annals of Science 36, 145-158.