Profile

Celia Kitzinger

Birth:

1956

Training Location(s):

PhD, University of Reading (1985)

MA, University of Oxford (1982)

BA, University of Oxford (1978)

Primary Affiliation(s):

University of York (2000-present)

Loughborough University (1992-2000)

University of Surrey (1991-1992)

University of East London (1988-1990)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

- Read Full Interview Transcript

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger & Sue Wilkinson: Equal Marriage Rights

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger & Sue Wilkinson: Heterosexuality

- PFV Interview with Sue Wilkinson: Real World Applications of Conversation Analysis

- PFV Interview with Sue Wilkinson: Focus Groups as Feminist Method

- PFV Interview with Sue Wilkinson: Feminist Identity and the POW Section

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: Coma and Disorders of Consciousness

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: The Lesbian and Gay Psychology Section of the BPS

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: The Social Construction of Lesbianism

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: Developing a Feminist Identity

Other Media:

Professional Websites

Celia Kitzinger at the University of York

Celia Kitzinger at Academia.edu

Other Websites

Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre

HealthTalk resource on Family Experiences of Vegetative and Minimally Conscious States

Videos

Interview with Celia Kitzinger and Jenny Kitzinger on “Coma, Consciousness, and Culture”

Career Focus:

Lesbian and feminist psychologies; equal marriage rights; conversation analysis; coma, disorders of consciousness, and end of life issues.

Biography

Celia Kitzinger was born on October 19, 1956 in Strasbourg, France. Her mother, Sheila Kitzinger, was a feminist and strong advocate for the right of women to have control over the conditions of childbirth, including their right to have home births. This heavily influenced Kitzinger’s feminist identity. Discussions about women’s rights, politics, ethics, prejudice, and stereotypes were extremely common in her home. As she put it, “I grew up in a household that was full of talk about women's rights, pregnant women demanding their rights, and arguments about politics, ethics. I was also brought up as a Quaker, so again that was a context in which there was a lot to talk about… I don't remember a time when I wasn't a feminist.”

Although she trained in psychology, challenging the assumptions of psychology – from within and without – became a lifelong endeavor. Kitzinger has an ambivalent relationship with the field to this day. At the age of 17, Kitzinger had her first experience with psychology’s tendency to problematize and pathologize aspects of the human experience. As she was becoming aware of her own identity as a lesbian, she began to do some research and found that most of the literature that addressed lesbianism presented lesbianism as a “perversion” and depicted lesbians as troubled individuals. These representations, of course, did not accord with her own experience and this directly influenced her study plans: “I chose to study psychology in order to challenge its representations of lesbianism.” At this point she had been expelled from two schools as a result of coming out as a lesbian. She was also placed in a mental hospital so that she could be “cured” of her sexual orientation. At the time, homosexuality had just been removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. As she explained, “I needed to enter psychology in order to challenge it from within.” Kitzinger returned to school to receive the relevant qualifications to pursue graduate education in psychology.

Kitzinger quickly discerned that in psychology, lesbians were left out of studies on humans; indeed, psychology seemed to have more to say about rats than people: “when I did my undergraduate degree, my main observation…was that lesbians were left out, insofar as we studied people at all…they were heterosexual people by presumption.” The psychological research that did exist was focused on demonstrating that gay people were really just as well-adjusted and capable as straight people. Kitzinger was not interested in the agenda of proving that gay women were “just as good” as straight women, and saw her lesbianism as aligning more closely with feminist challenges to stereotypical femininity and expectations of women.

During the 1990s, Kitzinger and fellow psychologists Sue Wilkinson, Louise Comely, and Rachel Perkins, began lobbying for a Lesbian and Gay Psychology Section (now the Psychology of Sexualities Section) in the British Psychological Society (BPS). During their struggle to have the section accepted, they received hate mail from other BPS registered psychologists. Some letters opposing the proposed new Section were published in the BPS professional journal, The Psychologist, under the title Are You Normal? In 1999, after nine years of work, and multiple rejections of the proposal, the Section was finally established, with Kitzinger as its inaugural Chair.

In 2004 Kitzinger and Wilkinson married in Canada (where Wilkinson was working for two years), shortly after same sex marriage became legal in the country. Returning to England the couple’s marriage was unrecognized by the British government. Although a Bill permitting civil partnerships between same sex couples was soon passed into law, marriage remained limited to heterosexual couples. This inequity spurred a period of sustained activism, including a legal challenge to the country’s stance on same sex marriage. In 2006 a judge ruled against Wilkinson and Kitzinger declaring that they “were indeed discriminated against compared to heterosexual couples and that discrimination was justified, in his view, under human rights legislation in order to protect the heterosexual unit of the family.” When same sex marriage became legal in 2013 the couple renewed their vows from nearly a decade earlier.

Located at Loughborough University in the 1990s, Kitzinger applied discourse analysis to issues of sexism and heterosexism. Later in the decade she switched her focus to conversation analysis, galvanized in part by hearing a colleague state that conversation analysis was “intrinsically anti-feminist.” This led her to spend time studying conversation analysis at the University of California, Los Angeles, with Emanuel Schegloff. Kitzinger became interested in the way that individuals reproduce the sexism and heteronormativity learned through society and the media in everyday language and conversation. This was an unorthodox approach to conversation analysis, but again Kitzinger chose to break the rules: “I was doing something, as usual, slightly perverse and shocking in the new discipline. And I called it Feminist Conversation Analysis, which I was told was an oxymoron.” Kitzinger returned to England and established the Feminist Conversation Analysis Unit at the University of York, where she is now a faculty member in the Department of Sociology.

In 2009 Kitzinger took on a new issue. After a serious car accident left her sister Polly with profound brain injuries, Kitzinger and her family were convinced that Polly would not want her life prolonged. However, under English law families are not the decision-makers for relatives who lose the capacity to make decisions for themselves and so they were legally unable to make the decision that medical treatment should be withdrawn. Without an Advance Decision (a legal document refusing treatments in advance of loss of capacity) or a Lasting Power of Attorney (assigning decision-making rights to someone else), all treatment decisions lie in the hands of physicians – or, ultimately, judges. In collaboration with another sister, Jenny Kitzinger, a Professor of Communications Research at Cardiff University, she set up the Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre (CDoC), an interdisciplinary research center that encompasses economics, law, history, literature, sociology, philosophy, and health care practice. The CDoC Centre aims to achieve changes in social policy and practice end of life issues and other concerns related to best interests decision-making and prolonged disorders of consciousness. For the first time, research in this area is including family members of affected individuals as co-producers of the research. Celia and Jenny are also working with health care practitioners and psychologists who are concerned about the way that end of life care is being managed and with senior lawyers and judges to try to improve the policy and practice for court applications on behalf of these patients.

Now working within a sociology department, Kitzinger does not feel constrained by some of the restrictions she felt when she was teaching psychology, including delivering a BPS-approved curriculum. But she does see the value of maintaining her connection to psychology. As she remarks, “I still have an ambivalent relationship to psychology, I see the power that it has and I want to influence it because it has that kind of power.”

In recognition of her significant contributions to psychology, Kitzinger received the BPS Research Board Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016. The chair of board referred to her as a "tour de force" who has impacted the British Psychological Society for the better (see The Pschologist, Sept 2016).

by Lisa Feingold (2016)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

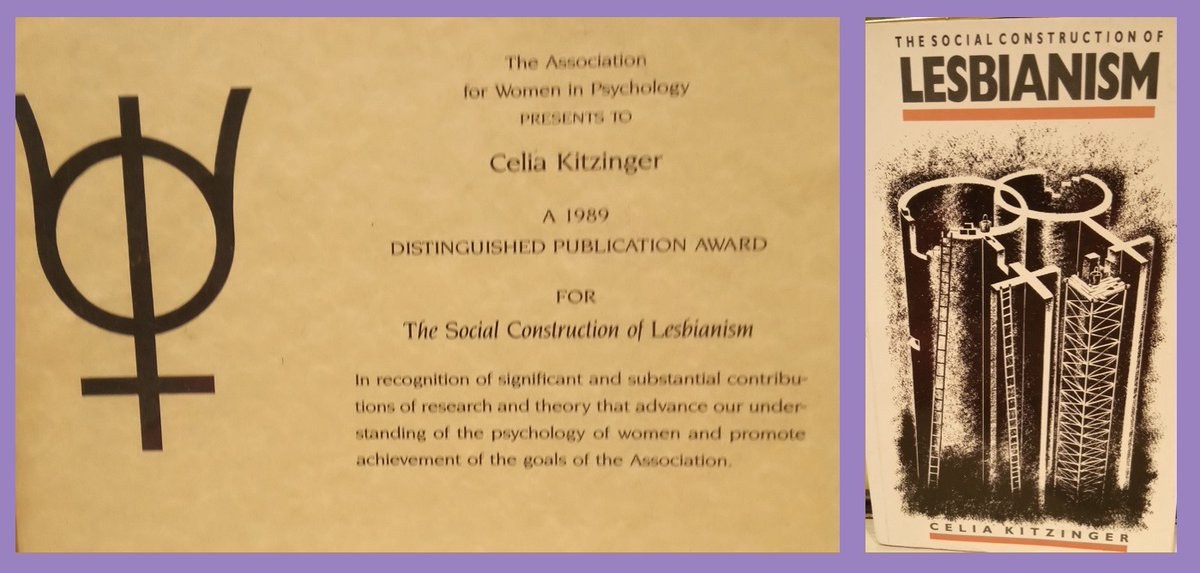

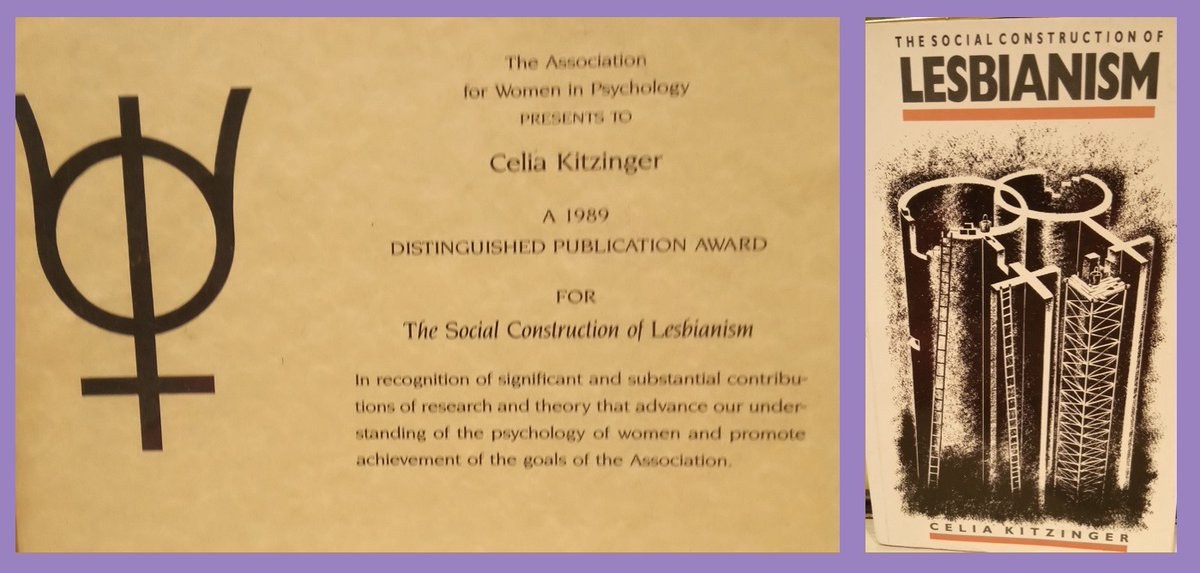

Kitzinger, C. (1987). The social construction of lesbianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kitzinger, C. (2000). Doing Feminist Conversation Analysis. Feminism & Psychology, 10(2), 163–193.

Kitzinger, C. (2004). Afterword: Reflections on three decades of lesbian and gay psychology. Feminism & Psychology, 14(4), 527-534.

Kitzinger, C. (2005). “Speaking as a heterosexual”: (How) does sexuality matter for talk-in-interaction? Research on Language and Social Interaction, 38(3), 221–265.

Kitzinger, C. (2005). Heteronormativity in action: Reproducing normative heterosexuality in ‘after hours’ calls to the doctor, Social Problems, 52(4), 477-498.

Kitzinger, C. (2015). Feminism and the ‘right to die’: Editorial introduction to the special feature. Feminism & Psychology, 25(1), 101-104.

Kitzinger, C., & Frith, H. (1999). Just say no? The use of conversation analysis in developing a feminist perspective on sexual refusal. Discourse & Society, 10(3), 293–316.

Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, J. (2014). Grief, anger and despair in relatives of severely brain injured patients: responding without pathologising. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(7), 627-631.

Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, J. (2015). Withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration from minimally conscious and vegetative patients: Family perspectives. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(2), 157–160.

Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, S. (2007). Birth trauma: Talking with women and the value of conversation analysis, British Journal of Midwifery 15(5), 256-264.

Kitzinger, C., & Perkins, R. (1993). Changing our minds: Lesbian feminism and psychology. New York: New York University Press.

Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1994). Re-viewing heterosexuality. Feminism & Psychology, 4(2), 330-336.

Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1995). Transitions from heterosexuality to lesbianism: The discursive production of lesbian identities. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 95–104.

Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (2004). The re-branding of marriage: Why we got married instead of registering a civil partnership. Feminism & Psychology, 14(1), 127-150.

Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (2005). Same-sex marriage and equality. The Psychologist, 18(5), 290-293.

Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (Eds.). (1993). Heterosexuality: A feminism & psychology reader. London: Sage.

Photo Gallery

Celia Kitzinger

Birth:

1956

Training Location(s):

PhD, University of Reading (1985)

MA, University of Oxford (1982)

BA, University of Oxford (1978)

Primary Affiliation(s):

University of York (2000-present)

Loughborough University (1992-2000)

University of Surrey (1991-1992)

University of East London (1988-1990)

Psychology’s Feminist Voices Oral History Interview:

- Read Full Interview Transcript

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger & Sue Wilkinson: Equal Marriage Rights

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger & Sue Wilkinson: Heterosexuality

- PFV Interview with Sue Wilkinson: Real World Applications of Conversation Analysis

- PFV Interview with Sue Wilkinson: Focus Groups as Feminist Method

- PFV Interview with Sue Wilkinson: Feminist Identity and the POW Section

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: Coma and Disorders of Consciousness

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: The Lesbian and Gay Psychology Section of the BPS

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: The Social Construction of Lesbianism

- PFV Interview with Celia Kitzinger: Developing a Feminist Identity

Other Media:

Professional Websites

Celia Kitzinger at the University of York

Celia Kitzinger at Academia.edu

Other Websites

Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre

HealthTalk resource on Family Experiences of Vegetative and Minimally Conscious States

Videos

Interview with Celia Kitzinger and Jenny Kitzinger on “Coma, Consciousness, and Culture”

Career Focus:

Lesbian and feminist psychologies; equal marriage rights; conversation analysis; coma, disorders of consciousness, and end of life issues.

Biography

Celia Kitzinger was born on October 19, 1956 in Strasbourg, France. Her mother, Sheila Kitzinger, was a feminist and strong advocate for the right of women to have control over the conditions of childbirth, including their right to have home births. This heavily influenced Kitzinger’s feminist identity. Discussions about women’s rights, politics, ethics, prejudice, and stereotypes were extremely common in her home. As she put it, “I grew up in a household that was full of talk about women's rights, pregnant women demanding their rights, and arguments about politics, ethics. I was also brought up as a Quaker, so again that was a context in which there was a lot to talk about… I don't remember a time when I wasn't a feminist.”

Although she trained in psychology, challenging the assumptions of psychology – from within and without – became a lifelong endeavor. Kitzinger has an ambivalent relationship with the field to this day. At the age of 17, Kitzinger had her first experience with psychology’s tendency to problematize and pathologize aspects of the human experience. As she was becoming aware of her own identity as a lesbian, she began to do some research and found that most of the literature that addressed lesbianism presented lesbianism as a “perversion” and depicted lesbians as troubled individuals. These representations, of course, did not accord with her own experience and this directly influenced her study plans: “I chose to study psychology in order to challenge its representations of lesbianism.” At this point she had been expelled from two schools as a result of coming out as a lesbian. She was also placed in a mental hospital so that she could be “cured” of her sexual orientation. At the time, homosexuality had just been removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. As she explained, “I needed to enter psychology in order to challenge it from within.” Kitzinger returned to school to receive the relevant qualifications to pursue graduate education in psychology.

Kitzinger quickly discerned that in psychology, lesbians were left out of studies on humans; indeed, psychology seemed to have more to say about rats than people: “when I did my undergraduate degree, my main observation…was that lesbians were left out, insofar as we studied people at all…they were heterosexual people by presumption.” The psychological research that did exist was focused on demonstrating that gay people were really just as well-adjusted and capable as straight people. Kitzinger was not interested in the agenda of proving that gay women were “just as good” as straight women, and saw her lesbianism as aligning more closely with feminist challenges to stereotypical femininity and expectations of women.

During the 1990s, Kitzinger and fellow psychologists Sue Wilkinson, Louise Comely, and Rachel Perkins, began lobbying for a Lesbian and Gay Psychology Section (now the Psychology of Sexualities Section) in the British Psychological Society (BPS). During their struggle to have the section accepted, they received hate mail from other BPS registered psychologists. Some letters opposing the proposed new Section were published in the BPS professional journal, The Psychologist, under the title Are You Normal? In 1999, after nine years of work, and multiple rejections of the proposal, the Section was finally established, with Kitzinger as its inaugural Chair.

In 2004 Kitzinger and Wilkinson married in Canada (where Wilkinson was working for two years), shortly after same sex marriage became legal in the country. Returning to England the couple’s marriage was unrecognized by the British government. Although a Bill permitting civil partnerships between same sex couples was soon passed into law, marriage remained limited to heterosexual couples. This inequity spurred a period of sustained activism, including a legal challenge to the country’s stance on same sex marriage. In 2006 a judge ruled against Wilkinson and Kitzinger declaring that they “were indeed discriminated against compared to heterosexual couples and that discrimination was justified, in his view, under human rights legislation in order to protect the heterosexual unit of the family.” When same sex marriage became legal in 2013 the couple renewed their vows from nearly a decade earlier.

Located at Loughborough University in the 1990s, Kitzinger applied discourse analysis to issues of sexism and heterosexism. Later in the decade she switched her focus to conversation analysis, galvanized in part by hearing a colleague state that conversation analysis was “intrinsically anti-feminist.” This led her to spend time studying conversation analysis at the University of California, Los Angeles, with Emanuel Schegloff. Kitzinger became interested in the way that individuals reproduce the sexism and heteronormativity learned through society and the media in everyday language and conversation. This was an unorthodox approach to conversation analysis, but again Kitzinger chose to break the rules: “I was doing something, as usual, slightly perverse and shocking in the new discipline. And I called it Feminist Conversation Analysis, which I was told was an oxymoron.” Kitzinger returned to England and established the Feminist Conversation Analysis Unit at the University of York, where she is now a faculty member in the Department of Sociology.

In 2009 Kitzinger took on a new issue. After a serious car accident left her sister Polly with profound brain injuries, Kitzinger and her family were convinced that Polly would not want her life prolonged. However, under English law families are not the decision-makers for relatives who lose the capacity to make decisions for themselves and so they were legally unable to make the decision that medical treatment should be withdrawn. Without an Advance Decision (a legal document refusing treatments in advance of loss of capacity) or a Lasting Power of Attorney (assigning decision-making rights to someone else), all treatment decisions lie in the hands of physicians – or, ultimately, judges. In collaboration with another sister, Jenny Kitzinger, a Professor of Communications Research at Cardiff University, she set up the Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre (CDoC), an interdisciplinary research center that encompasses economics, law, history, literature, sociology, philosophy, and health care practice. The CDoC Centre aims to achieve changes in social policy and practice end of life issues and other concerns related to best interests decision-making and prolonged disorders of consciousness. For the first time, research in this area is including family members of affected individuals as co-producers of the research. Celia and Jenny are also working with health care practitioners and psychologists who are concerned about the way that end of life care is being managed and with senior lawyers and judges to try to improve the policy and practice for court applications on behalf of these patients.

Now working within a sociology department, Kitzinger does not feel constrained by some of the restrictions she felt when she was teaching psychology, including delivering a BPS-approved curriculum. But she does see the value of maintaining her connection to psychology. As she remarks, “I still have an ambivalent relationship to psychology, I see the power that it has and I want to influence it because it has that kind of power.”

In recognition of her significant contributions to psychology, Kitzinger received the BPS Research Board Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016. The chair of board referred to her as a "tour de force" who has impacted the British Psychological Society for the better (see The Pschologist, Sept 2016).

by Lisa Feingold (2016)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

Kitzinger, C. (1987). The social construction of lesbianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kitzinger, C. (2000). Doing Feminist Conversation Analysis. Feminism & Psychology, 10(2), 163–193.

Kitzinger, C. (2004). Afterword: Reflections on three decades of lesbian and gay psychology. Feminism & Psychology, 14(4), 527-534.

Kitzinger, C. (2005). “Speaking as a heterosexual”: (How) does sexuality matter for talk-in-interaction? Research on Language and Social Interaction, 38(3), 221–265.

Kitzinger, C. (2005). Heteronormativity in action: Reproducing normative heterosexuality in ‘after hours’ calls to the doctor, Social Problems, 52(4), 477-498.

Kitzinger, C. (2015). Feminism and the ‘right to die’: Editorial introduction to the special feature. Feminism & Psychology, 25(1), 101-104.

Kitzinger, C., & Frith, H. (1999). Just say no? The use of conversation analysis in developing a feminist perspective on sexual refusal. Discourse & Society, 10(3), 293–316.

Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, J. (2014). Grief, anger and despair in relatives of severely brain injured patients: responding without pathologising. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(7), 627-631.

Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, J. (2015). Withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration from minimally conscious and vegetative patients: Family perspectives. Journal of Medical Ethics, 41(2), 157–160.

Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, S. (2007). Birth trauma: Talking with women and the value of conversation analysis, British Journal of Midwifery 15(5), 256-264.

Kitzinger, C., & Perkins, R. (1993). Changing our minds: Lesbian feminism and psychology. New York: New York University Press.

Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1994). Re-viewing heterosexuality. Feminism & Psychology, 4(2), 330-336.

Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1995). Transitions from heterosexuality to lesbianism: The discursive production of lesbian identities. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 95–104.

Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (2004). The re-branding of marriage: Why we got married instead of registering a civil partnership. Feminism & Psychology, 14(1), 127-150.

Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (2005). Same-sex marriage and equality. The Psychologist, 18(5), 290-293.

Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (Eds.). (1993). Heterosexuality: A feminism & psychology reader. London: Sage.