Profile

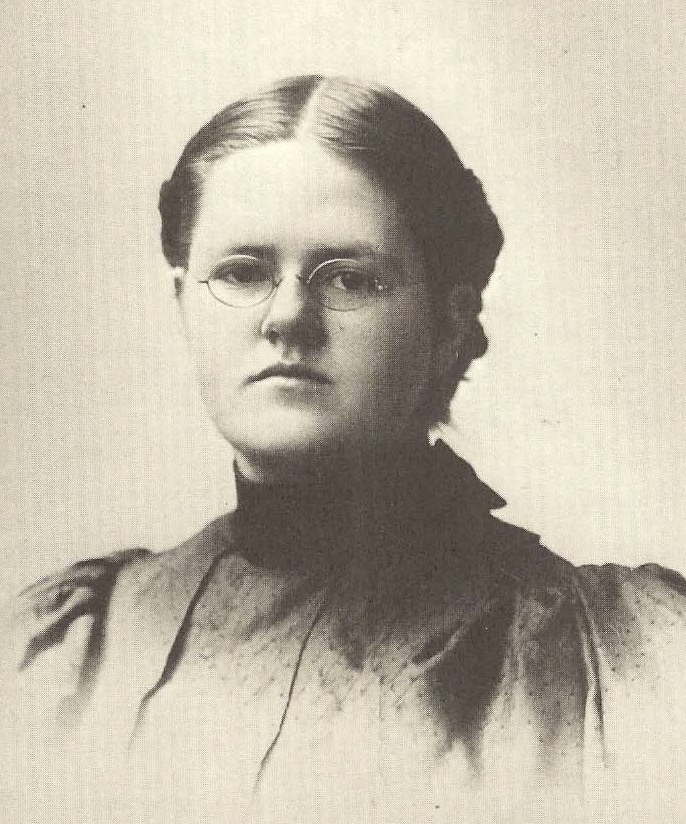

Frances Rousmaniere

Birth:

1876

Death:

1964

Training Location(s):

PhD, Radcliffe College (1906)

MA, Wellesley College (1904)

BA, Wellesley College (1900)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Bennington College (1943-1945)

Smith College (1908-1910)

Mount Holyoke College (1906-1908)

Other Media:

Archival Collections

Career Focus:

Developmental psychology; philosophy; education.

Biography

Frances Rousmaniere was born near Boston to a successful businessman and his wife. Rousmaniere's college experience was interrupted by illness: her younger brother fell ill, and since her mother's heart trouble made her unable to nurse him, Rousmaniere returned home to care for her brother. Eventually she was able to return to school, and in 1900 Rousmaniere graduated from Wellesley College. At Wellesley she met Mary Whiton Calkins, who shared her inclination towards academic work and a desire to better the world. Calkins and Rousmaniere would remain lifelong friends.

When Rousmaniere's parents died around 1903, she moved in with a Harvard medical school professor's family in Cambridge and began graduate studies in philosophy at Radcliffe College. She completed a Ph.D. in 1906, but this was only after her professors, George Herbert Palmer and Josiah Royce encouraged her to apply for the degree when they realized she had enough classes to qualify. She had taken the classes for her own enjoyment, and had no professional plans. However, despite this Rousmaniere taught for four years at Mt. Holyoke and Smith Colleges until her marriage to a fellow academic she had met at Harvard: Arthur Dewing, a professor at Harvard's business school and Simmons College. Rousmaniere then took on the typical faculty wife role by supporting her husband's academic work, helping him write articles and manage his correspondence. She also was occupied by their three daughters, who were born within the first six years of their marriage. Rousmaniere maintained her friendships with her old colleagues but she had a distaste for women's clubs, which she found impersonal and intellectually dissatisfying. Instead, life for Rousmaniere revolved around her family and close friends.

Rousmaniere took her domestic duties seriously, devoting a great deal of thought to developing more efficient and satisfying housekeeping methods while reducing her need for servants. She recorded her efforts in a journal, recommending such measures as simplifying the family's lifestyle and getting the husband and children to help with chores. Rousmaniere suggested some practical ways to make routine tasks less odious, such as "When I am washing dishes, I hope it will always be possible for my husband to read aloud to me-often, if not always" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 196).

Rousmaniere saw family as consisting of four coordinate claims: the husband's career, the wife's life, the children's lives, and the husband's life. The husband's career should have priority, she believed, but socially ambitious women were often guilty of pushing their husbands to sacrifice too much for their career. They should support and cooperate with their husband's efforts, she wrote, but not push him to give up family life for career. Although Rousmaniere thought a hobby or profession for the wife was useful for once the children were grown, she didn't think a career was beneficial for the children. In general, it did not enhance the family's standing and could introduce a dangerous uncertainty into girls' lives. Girls were hungry for "the chance to bring something real to pass which shall indicate their value in the world" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 196-197), Rousmaniere believed, and motherhood and homemaking would satisfy that hunger.

Yet despite these views, Rousmaniere often found herself dissatisfied with a life filled with such activities. She described herself as "bewildered by the multiplicity of claims of 'modern life,'" which absorbed all her time (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 197). In 1923 she reported to her fellow Wellesley alumnae "I do nothing notable along civic or other lines, much less than my interests would lead to. Ordinary living challenges all my resources so far" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 197). In spite of her busyness, Rousmaniere longed for meaningful intellectual activities; "I feel hungry all the time," she wrote (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 197). Journaling was an attempt to deal with this hunger, although she thought that talking with her husband also helped.

Over the years Rousmaniere did a little teaching as an assistant in her husband's classes, and in 1942, at age sixty-seven, she returned to teaching full time. There was a shortage of teachers during World War II and Rousmaniere got a position teaching mathematics at Bennington College in Vermont, the school one of her daughters had attended a decade earlier. This meant relocating to Vermont, and though Arthur Dewing was supportive, he stayed in Cambridge. Rousmaniere taught for three years before her younger sister's illness brought an end to this re-entry into professional life.

Frances Rousmaniere died in Cambridge, Massachusetts on February 20, 1964, just months after Betty Friedan's publication of The Feminine Mystique.

by Elissa Rodkey (2010)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Frances Rousmaniere

Rousmaniere, F.H. (1906). Certainty and attention. Harvard Psychol. Stud. 2, 277-291.

Rousmaniere, F.H. (1906). A definition of experimentation. J. of Phil., Psychol. 3, 673-679.

Rousmaniere, F.H. (1942). Pasteur: A study in method. The Scientific Monthly, 54, 529-536.

About Frances Rousmaniere

Rosenzweig, L. W. (1999). Another self: Middle-class American women and their friends in the twentieth century. New York: NYU Press.

Scarborough, E. & Furumoto, L. (1987). Untold lives: The first generation of American women psychologists. New York: Columbia University Press.

Frances Rousmaniere

Birth:

1876

Death:

1964

Training Location(s):

PhD, Radcliffe College (1906)

MA, Wellesley College (1904)

BA, Wellesley College (1900)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Bennington College (1943-1945)

Smith College (1908-1910)

Mount Holyoke College (1906-1908)

Other Media:

Archival Collections

Career Focus:

Developmental psychology; philosophy; education.

Biography

Frances Rousmaniere was born near Boston to a successful businessman and his wife. Rousmaniere's college experience was interrupted by illness: her younger brother fell ill, and since her mother's heart trouble made her unable to nurse him, Rousmaniere returned home to care for her brother. Eventually she was able to return to school, and in 1900 Rousmaniere graduated from Wellesley College. At Wellesley she met Mary Whiton Calkins, who shared her inclination towards academic work and a desire to better the world. Calkins and Rousmaniere would remain lifelong friends.

When Rousmaniere's parents died around 1903, she moved in with a Harvard medical school professor's family in Cambridge and began graduate studies in philosophy at Radcliffe College. She completed a Ph.D. in 1906, but this was only after her professors, George Herbert Palmer and Josiah Royce encouraged her to apply for the degree when they realized she had enough classes to qualify. She had taken the classes for her own enjoyment, and had no professional plans. However, despite this Rousmaniere taught for four years at Mt. Holyoke and Smith Colleges until her marriage to a fellow academic she had met at Harvard: Arthur Dewing, a professor at Harvard's business school and Simmons College. Rousmaniere then took on the typical faculty wife role by supporting her husband's academic work, helping him write articles and manage his correspondence. She also was occupied by their three daughters, who were born within the first six years of their marriage. Rousmaniere maintained her friendships with her old colleagues but she had a distaste for women's clubs, which she found impersonal and intellectually dissatisfying. Instead, life for Rousmaniere revolved around her family and close friends.

Rousmaniere took her domestic duties seriously, devoting a great deal of thought to developing more efficient and satisfying housekeeping methods while reducing her need for servants. She recorded her efforts in a journal, recommending such measures as simplifying the family's lifestyle and getting the husband and children to help with chores. Rousmaniere suggested some practical ways to make routine tasks less odious, such as "When I am washing dishes, I hope it will always be possible for my husband to read aloud to me-often, if not always" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 196).

Rousmaniere saw family as consisting of four coordinate claims: the husband's career, the wife's life, the children's lives, and the husband's life. The husband's career should have priority, she believed, but socially ambitious women were often guilty of pushing their husbands to sacrifice too much for their career. They should support and cooperate with their husband's efforts, she wrote, but not push him to give up family life for career. Although Rousmaniere thought a hobby or profession for the wife was useful for once the children were grown, she didn't think a career was beneficial for the children. In general, it did not enhance the family's standing and could introduce a dangerous uncertainty into girls' lives. Girls were hungry for "the chance to bring something real to pass which shall indicate their value in the world" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 196-197), Rousmaniere believed, and motherhood and homemaking would satisfy that hunger.

Yet despite these views, Rousmaniere often found herself dissatisfied with a life filled with such activities. She described herself as "bewildered by the multiplicity of claims of 'modern life,'" which absorbed all her time (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 197). In 1923 she reported to her fellow Wellesley alumnae "I do nothing notable along civic or other lines, much less than my interests would lead to. Ordinary living challenges all my resources so far" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 197). In spite of her busyness, Rousmaniere longed for meaningful intellectual activities; "I feel hungry all the time," she wrote (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 197). Journaling was an attempt to deal with this hunger, although she thought that talking with her husband also helped.

Over the years Rousmaniere did a little teaching as an assistant in her husband's classes, and in 1942, at age sixty-seven, she returned to teaching full time. There was a shortage of teachers during World War II and Rousmaniere got a position teaching mathematics at Bennington College in Vermont, the school one of her daughters had attended a decade earlier. This meant relocating to Vermont, and though Arthur Dewing was supportive, he stayed in Cambridge. Rousmaniere taught for three years before her younger sister's illness brought an end to this re-entry into professional life.

Frances Rousmaniere died in Cambridge, Massachusetts on February 20, 1964, just months after Betty Friedan's publication of The Feminine Mystique.

by Elissa Rodkey (2010)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Frances Rousmaniere

Rousmaniere, F.H. (1906). Certainty and attention. Harvard Psychol. Stud. 2, 277-291.

Rousmaniere, F.H. (1906). A definition of experimentation. J. of Phil., Psychol. 3, 673-679.

Rousmaniere, F.H. (1942). Pasteur: A study in method. The Scientific Monthly, 54, 529-536.

About Frances Rousmaniere

Rosenzweig, L. W. (1999). Another self: Middle-class American women and their friends in the twentieth century. New York: NYU Press.

Scarborough, E. & Furumoto, L. (1987). Untold lives: The first generation of American women psychologists. New York: Columbia University Press.